- Home

- Ann Wilson

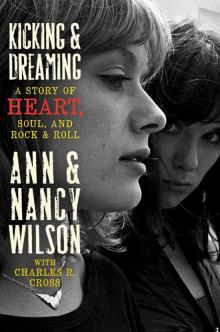

Kicking and Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock and Roll

Kicking and Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock and Roll Read online

Dedication

To Hannah, whose

pioneering spirit lives on.

Contents

Cover

Title

Dedication

Prologue

1 The Lady Axe Killer

2 The Big Five

3 Dust Off Your Shoes

4 Meet the Beatles

5 Blood Harmony

6 Cryin’ in the Chapel

7 A Boy and His Dog

8 She’s Here to Sing

9 The Whisper That Calls

10 The Impossible Perfect Thing

11 The Northern Lights

12 Burn to the Wick

13 Natural Fantasies

14 Ocean upon the Sky

15 Blows Against the Empire

16 Heartless

17 Leave It to Cleavage

18 Junior’s Farm

19 The Battle of Evermore

20 Live from the DoubleTree Inn

21 The Other Half of the Sky

22 The Boys March In

23 Send Up a Flare

24 I Can See Russia

25 Hope and Glory

26 Glimmer of a Dream

Photo Insert

Acknowledgments

Credits

Heart Is

Copyright

Permissions

About the Publisher

Prologue

L’homme magique, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

OCTOBER 18, 1975

Our journey starts with Ann’s encounter with the

Devil’s nightclub and poisoned food. Nancy, meanwhile,

battles the demons of disco, orange jumpsuits, and flames

both good and evil. . . .

ANN WILSON

I never thought much about it at the time, but looking back it seems odd that our career came crashing apart and then came magically back together in a club named Lucifer’s.

Robert Johnson, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Jimmy Page. You might have expected all of them on the bill at Lucifer’s, in Calgary, Canada. But in October 1975, the red-flamed letters on the club’s marquee read FROM VANCOUVER . . . DREAMBOAT ANNIE recording artists: Heart. Never mind that my sister Nancy and I were from the Seattle suburbs, temporarily transplanted to Canada.

The red letters in the sign, with a couple of burned-out bulbs, could have represented what was happening to Heart’s career. We had been red-hot for a time, but our flame was suddenly flickering. Dreamboat Annie had come out two months before, and “Crazy On You” earned decent airplay in Vancouver. But the album had been released only in Canada, and with very limited distribution. Our label had a staff of two and operated out of a desk in the corner of Mushroom Studios.

We had come to Vancouver three years before with a plan for stardom. The plan had worked: Slowly, steadily, we had moved forward. As we joked among ourselves, we had become “the number-one cabaret band in Vancouver.” That meant we played nightclubs six nights a week, five sets a night. Those gigs had paid off artistically, if not financially. If one believes the theory Malcolm Gladwell puts forth in his book Outliers, that if you spend ten thousand hours doing something you get good at it, Heart had become very good, indeed.

But we were also broke. Every Canadian dollar we earned went into instruments, amplifiers, speakers, or our van, which often collided with wildlife. At that moment our van needed costly repairs from a moose accident before it could make it back home from Calgary.

Our manager—and my boyfriend—Michael Fisher, aka “the Magic Man,” was constantly pushing his “five-year plan,” which was to build Heart from a nightclub act to an album band, to stardom in Canada, and finally to U.S. success. Everything had worked accordingly until our album came out and failed to take off immediately, and our career went into a stall phase.

Since we couldn’t play Vancouver clubs every week without wearing out our welcome, we had to take any gig we could find. We played taverns, roadhouses, keggers, private parties. We played dozens of high school dances. We once played a prom in North Vancouver where Michael J. Fox was the student body president. He came back before the show to shake our hands. “That kid is going places,” Nancy said of the short, good-looking boy with a strong handshake. She was right.

We took the gig at Lucifer’s in Calgary, a fourteen-hour drive from Vancouver, because it was the only offer we had right then. We were booked for a two-week run, five sets a night, six nights a week. That first night, we drew a packed house on a typically slow Monday. But after the show, the club manager lectured us that we had brought in “the wrong crowd.” Our fans hadn’t eaten enough food, and they drank beer rather than pricier hard liquor. He also said we played too loud.

As the week went by, it was more of the same. We played to big houses, yet the manager thought we should play more covers. Disco was big at the time, and he suggested we’d be more successful if we dropped our original songs entirely and played only disco hits. Playing in this club felt as if we could have been working at an insurance company with a demanding boss. This wasn’t rock and roll.

On Saturday night, our sixth in a row at Lucifer’s, with another week to go, the club treated us to dinner before the show. We were thankful for it, because we often ate brown rice cooked on a camp stove in our hotel room. But the food the club served had a suspicious odor. Actually, it tasted like Pine-Sol disinfectant. They had either washed the serving plates in Pine-Sol, or the cleaner had somehow gotten into the food. It was disgusting.

I began to wonder if Lucifer’s was trying to poison us because we weren’t a disco band.

NANCY WILSON

I had only joined Heart two years before, after dropping out of college in Oregon. It had always been Ann and my goal to be in a band together, but I joined somewhat reluctantly and transplanted myself up there. I wanted to play with my sister, and I, like everyone else in the band, had drunk the Kool-Aid and believed that we could be the best live band in Canada.

That belief was not shared by the manager of Lucifer’s, who kept telling us to play disco hits. When I first joined, we would occasionally cover the Bee Gees “Nights on Broadway” or “Jive Talkin’ ” to get people on the dance floor during our opening set. But by 1975, we were trying to do more original material—Dreamboat Annie songs. It was our statement to the world that disco was not going to get us.

As the week went on, we got more criticism. The manager said we didn’t dress well enough. The Stylistics had been there before us, and the manager pointed to a picture of them on the wall, with their matching suits, and told us we’d be more successful if we dressed like them. Another band was pictured wearing orange pantsuits. In that era we usually wore jeans with Kimono-styled tops. It was hippie, but it also had flair. It was our style, and not a fabrication by a record label, or a club manager. We wanted to look sexy, but we did not want to dress in a way that objectified us.

The fact that we were women, and sisters, always got a lot of attention, but there was a lot of male energy in Heart, as well. Onstage, Roger Fisher, our lead guitar player, would strut around wearing a little leather vest showing off his rock-hard abs, and he played a lot like Jimmy Page. He was a brilliant player, but he had a temper and could be a wild man. By Saturday night, we were exhausted, and we were sick of being ripped into for just being Heart. Before the show, Roger got a bottle of Grand Marnier from the bar. He poured it out on the dressing room floor. Then he lit it on fire. It was just like Jimi Hendrix at Monterey.

In the dressing room, the manager had posted a l

ong list of “House Rules” that ran the entire length of one wall. They read:

No bad language.

No spitting.

No chewing gum.

No smoking.

No drinking.

No lighters.

No dungarees.

No groupies.

No drugs.

No dogs.

As I read this, I looked at our band. We were wearing jeans, smoking cigarettes and pot, drinking, and our guitar player had just set the floor on fire. But the regulation that bothered me the most was “No dogs.” Dogs have always been part of the Wilson family, and any club that didn’t allow a sweet dog backstage was just heartless.

Roger went up and at the bottom of the list he wrote:

“NO FUN. THIS PLACE SUCKS.”

Because we were two women playing rock music, we had come against barriers at every step. “Is your guitar really plugged in?” I’d be asked many times. “You play pretty good for a girl,” guys would constantly say. Our skill at doing Led Zeppelin covers had earned us the nickname “Little Led Zeppelin,” but we also knew guys called us “Led Zeppelin with tits,” behind our backs. We naively thought if we were good at our instruments, we’d be judged as musicians, and not by gender. We had no idea that being females in rock ’n’ roll would be an issue we would face at every turn.

But that kind of struggle we were used to. Lucifer’s represented a different kind of battle. It had less to do with the fact that we were women and more to do with a divide between what was then the disco-dominated music world, and anyone trying to do anything else. The club felt like the establishment, and the establishment felt like the enemy. It was the absolute low. I thought, “I left college for this?”

By Saturday, the tension was obvious. When we went onstage, I could see that something was off with Ann. She had that glint of anger in her eye. Ann has never liked anyone to tell her that she can’t do something. She had struggled harder than anyone to make Heart happen, and things weren’t working out. She looked scorned, and I had long ago learned that Ann Wilson scorned was a force of nature.

Ann started the set by asking Michael Fisher, who was doing the sound, to turn us up. She knew this would make the manager upset. Then she addressed the crowd:

“How’d your dinners taste? Mine tasted like Pine-Sol. I think they washed the dishes with Pine-Sol.” And then she launched into “Crazy On You.” It was the first time during that stand at Lucifer’s that we had opened a set with a song of our own. The crowd, our beer-only fans, went bonkers. It was us, our song, our words, our chords, and not disco. The instant Ann started singing, I could see her fury had subsided, and she was back into the music, soothed by it.

Not that the owner noticed. When we came offstage for the night, he was furious. He hauled Ann, along with Michael Fisher, into his office.

ANN

I knew we were going to get yelled at, but what the club owner said surprised me: “You’re fired. Clear out of your rooms tonight. And you won’t be getting the rest of your pay.”

“We have a contract!” Michael protested.

“Not anymore,” he said, ripping the contract up.

We went back to the dressing room and told the band. The dressing room was made of wood veneer. Someone in the band kicked a wall, and his foot went right through it, leaving a gaping hole.

We’d come so far, and it had ended at this. Our van couldn’t make it home. We were getting kicked out of our hotel. I had just been fired from a gig, and I had never been fired from anything in my life. My band, my life, had fallen apart in a club named after the Devil in the middle of the Canadian prairie.

Walking back to my room, I couldn’t bear the idea that I would have to tell our parents as well. Our parents had always been supportive of music but they had been suspicious that I was corrupting Nancy, bringing her into an adult world of rock ’n’ roll too fast, too soon. And here, in Lucifer’s, their fears had come true.

As I was packing up my room, with no idea where we were going, the phone rang. It was Shelley Siegel, promotions manager for Mushroom Records. “Any chance you can get out of that contract in Calgary?” he said.

“The contract just got ripped up,” I said. “We were fired.”

“Great,” he said, as if that were the best news he’d heard all day. “You’ve got a gig opening up for Rod Stewart for two shows, starting in Montreal. It’s in four days, and Montreal is twenty-three hundred miles away. Do you think you can get there?”

“We’ll get there.”

The only way we could make the journey in time was by train. We carted all our gear onto a rail car and ended up having the car to ourselves for the three-day ride. It turned into a day and night jam, with everyone in the band grabbing acoustic instruments. We played all the songs we’d grown up on. It was “Here Comes the Sun,” “Michelle,” “House of the Rising Sun,” and “Gloria” all the way to Montreal. At that point, the band was one big family. It was the sweetest, most innocent time Heart ever had. It was all joy and all possibility.

When we got to Montreal, I felt like I was stepping into a fairy tale. It seemed more French than Paris. The whole city was draped in romance. Every street corner dripped with poetry. It was like it was surrounded with torches.

The venue was gigantic. We’d played big nightclubs before, but the only time I’d even been in a venue as big as the Forum was when I saw the Beatles play at the Seattle Center Coliseum. At showtime I walked onstage, but it was so bright out there I thought the house lights were still on. I could see fans standing up and cheering. Every person who wasn’t clapping was holding up a lighter.

I thought that Rod Stewart must have come onstage behind us. I turned around but all I saw were my bandmates, who looked stunned. Nancy was more astonished than I had ever seen her.

The fans wouldn’t quiet down, so I walked to the side of the stage and asked Michael Fisher what was happening. “One of the French-language radio stations has been playing our album,” he said. “It’s a hit!”

Four days before, I had been eating Pine-Sol–laden food, had been fired from my first gig ever, and had been busted flat in Calgary. Now I was walking onstage in a sold-out arena of eighteen thousand people who loved us before I even opened my mouth. Michael Fisher later told me that the moment had been electric for him as well because it was “proof of concept”—that the plan he had come up with, which had been executed by everyone in Heart all those nights in those smoky nightclubs, had worked. It was one radio station, and one whose listeners weren’t even English-speakers, but it was proof it was possible for us to find an audience.

I walked back to the microphone on the Forum stage and put both hands on it to steady myself. I paused to catch my breath. But I didn’t start singing. Instead, I said the words in French that someone backstage had cued me with. “Cette chanson s’appelle ‘L’ Homme Magique.’ ” In my broken French, I was telling them the song was called “Magic Man.” The crowd went absolutely bananas. As the guitar solo started the song, everyone in the place sang along.

It was only one city in the world, but for the first time we were stars.

1

The Lady Axe Killer

The secret family history of kidnapping, scalping, and

revenge killing, and those pesky, annoying, irrelevant

“Women who Rock” questions. . . .

NANCY WILSON

In the four decades that Ann and I have been in music, we’ve been asked countless times what it’s like to be “a woman in rock.” This question is asked in virtually every interview we do, by men and by women. We sit politely and try to come up with an answer we hope will encourage others. But what I really want to do is scream questions in reply, like “What’s it like to be a human being in rock? What’s it like to be a human being on the planet?”

In forty years, we’ve never come up with the perfect answer to the “woman in rock” question or the other common question: “Why did you first think women c

ould rock?” We have no perfect answer for the simple reason that we never thought gender was a barrier to picking up guitars. We started playing because we loved music. If we would have known how difficult it would be to be women fronting a band, it might have stopped us. But probably we would have done it anyway.

Yet there is a secret chapter in our family history that might explain our urge to fight against the norm, so to speak. The story itself is in American history textbooks, but our connection to it has never been revealed. It has long been part of our family lore, passed down to us. I’ve since passed the story on to my children, as has Ann, and my other sister Lynn. It is a story of murder, kidnapping, and revenge, with enough gruesome details to make any Behind the Music episode look tame. So imagine an alternative world, where Ann and I are sitting down with an interviewer who asks: “Why did you think you could be a woman in rock?”

Our answer: “Because we are descended from a notorious woman who murdered men with a hatchet, scalped them, and later sold their scalps for a reward.”

My bad joke inside the Heart tour bus has long been that I am not the first family member to slay people with an axe. The original axe slayer was Hannah Dustin, our great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandmother. Dustin was our mother’s maiden name.

I first heard Hannah’s tale from my mother when I was five. Before I picked up a guitar, I must have heard the story a hundred times. Family gatherings were always important to the Dustins, and the tale would have slightly different shading whether an aunt, or uncle, or my mom was telling it. The basic framework was always the same, though, and always horrific and shocking. In some strange way, because Hannah’s actions were so unexpected, and so rare for a woman, I always felt secretly proud of murderous Hannah.

Her infamy began in March 1697 in Haverhill, Massachusetts, not far from Salem. During King William’s War, French emissaries bribed the Abenaki tribe to attack an English settlement. Twenty-seven colonists were killed and thirteen taken hostage. Hannah’s husband escaped with eight of their children, but she and her newborn daughter Martha were kidnapped. The hostages were marched toward Quebec. On the way the Indians killed six-day-old Martha by smashing her head against a tree. Hannah had to watch as her newborn was murdered in front of her.

The Alembic Plot: A Terran Empire novel

The Alembic Plot: A Terran Empire novel Zeta Exchange: A Terran Empire story

Zeta Exchange: A Terran Empire story Teams: A Terran Empire story

Teams: A Terran Empire story Youngling: A Terran Empire story

Youngling: A Terran Empire story Concordance: A Terran Empire concordance

Concordance: A Terran Empire concordance New Year's Wake: A Terran Empire story

New Year's Wake: A Terran Empire story Thakur-na: A Terran Empire story

Thakur-na: A Terran Empire story Hostage: A Terran Empire story

Hostage: A Terran Empire story Ambush: A Terran Empire vignette

Ambush: A Terran Empire vignette Kicking and Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock and Roll

Kicking and Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock and Roll